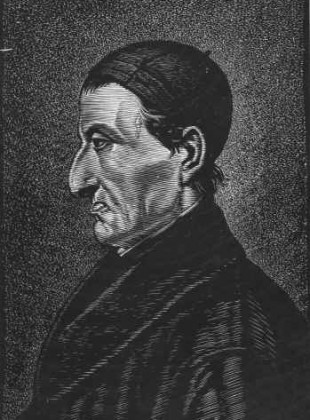

It’s the birthday of Fr. Luigi Taparelli d’Azeglio (1793–1862), the man who coined the phrase “social justice.” Here’s a nice little piece by Ryan Messmore in First Things which summarizes his contribution. Give it a quick read and consider the implications for architecture.

He taught:

… that human beings naturally join together in groups. “The social fact, considered at its maximum generality, presented us subjects as intelligent beings and human society as men, that is to say made of intelligence and sense,” Taparelli says, and because of his intelligence and sense, men are able to share common ideas which produces a “unity of will” to achieve various ends and this is “the essential idea of society.”

Some of these societies, however, are more natural and intimate than others. We come together not just in cities and states, but first and most importantly in families, neighborhoods, religious bodies, clubs (or, in his day, guilds) and a variety of informal organizations. Through these natural associations, people strive to meet the basic goals and goods of life.

For society to be organized, it must be organic, that is, it is a body which is composed of a variety of organs each of which has a purpose.

Taparelli believed that people have the right to freely form different levels of association and to interact through them to fulfill needs and accomplish necessary tasks. Each of these social spheres, institutions, or consortia has its own proper identity and purpose. According to Taparelli, “every consortium must conserve its own unity in such a way as to not lose the unity of the larger whole,” but at the same time “every higher society must provide for the unity of the larger whole without destroying the unity of the consortia.”

This is a beautiful summary of the principle of subsidiarity.

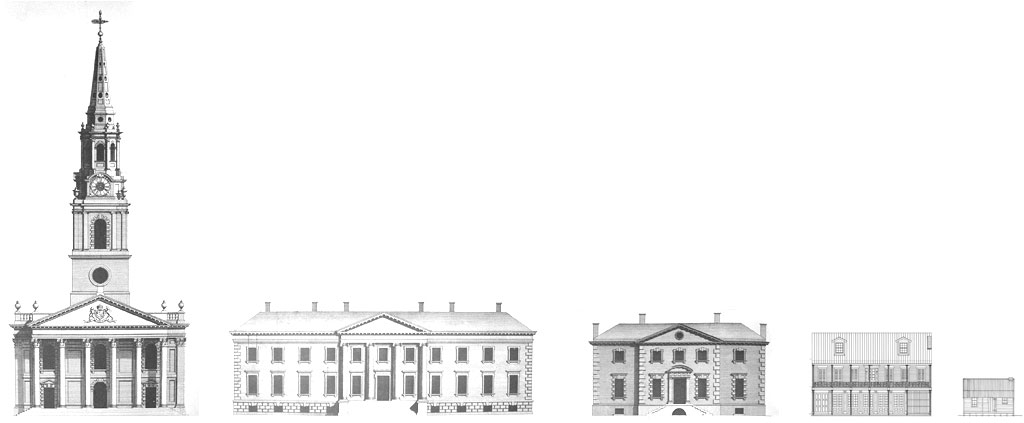

What are the implications for architecture, then? Simple: architecture will naturally be a reflection of a society’s just ordering. Building on Taparelli: the architecture of a particular institution will express the unity of that institution, as well as the unity of the whole society of which that institution is a part.

So a city must have a certain degree of architectural unity about it if it is to be just. It cannot be a collection of fragments, each the product of an individual’s rootless personal expression. Such supposedly free expression is in fact unjust in that it does not respect the rightful claims of the whole.

That unity is supplied by a respect for the architectural tradition. It’s not a formulaic unity as the tradition is continually refined and perfected. And certainly there is ample room for personal expression. In fact, personal expression is at its most powerful in the context of a tradition which provides traction. Just ask Michelangelo. Leon Battista Alberti, the great 15th century architect and canonist, called this coherence between the whole and the parts the principle of congruity. He said:

The Business and Office of Congruity is to put together Members differing from each other in their Natures, in such a Manner, that they may conspire to form a beautiful Whole…

Of course it would be beautiful! In short, a building which is socially just is:

1. Expressive of the identity of the institution it represents, be it the family, the neighborhood, the corporation, or the state

2. Expressive of the whole of which the institution is a part

3. Orderly, hierarchical, and organic (in the true sense of the word) in and of itself

4. Respectful of the tradition which provides the context And, if the building gets all that right, it’s almost sure to achieve…

5. Beautiful

I’m in absolute agreement. Well said, Dino!