Look back at the sweeping canvas that is the whole history of art and architecture and focus on the broadest strokes. You will see Victorian, Neo-classical, Baroque, Renaissance, Gothic, Romanesque, Byzantine, Roman, Greek, Egyptian… You can see as far back as about 5,000 years. Each generation has added a broad panel to the historical canvas, building on what came before, both literally–maintaining and adding to the physical patrimony–and figuratively–passing on ideas and traditions, “monuments more lasting than bronze.” With the passage of time some things changed: the pendulum of taste swung between the sumptuous and the severe, technology advanced allowing for novel forms, artistic experimentation produced both successes and failures, and conventions were born and faded away. Yet one can say that the whole canvas is in a certain respect quite harmonious. In terms of attitude and general approach to the design of buildings there is an overriding consistency, and the innumerable panels of this canvas blend seamlessly together. All of them, that is, with the exception of the one tiny panel added in the last century.

From its inception, Modernism set itself radically apart from the whole history which preceded it. “A great epoch has begun. There exists a new spirit,” preached the journalist/architect Charles-Edouard Jeanneret in 1921. That spirit of discontinuity continues to be felt today, even with buildings that are considered historical by government preservation bodies. What is it that explains this discordance? Why do modernist buildings resist fitting in?

If I may engage you a smattering of philosophy, there are two basic ways of thinking of the world around you. The first way works as follows. You are conceived and born, and as an infant, you are flooded with new sensations. You touch, hear, taste, see, and smell things for the first time, and in doing so you discover the world around you–and you also discover yourself. We have all seen babies studying their own hands as if they were foreign objects. Aristotle taught that all knowledge comes to us first through sense experience. Even the very knowledge of our personal existence comes to us through the senses. One can say, in fact, that if we were born without senses–no touch, no sight, no smell, no hearing, no taste–we would never learn that we existed!

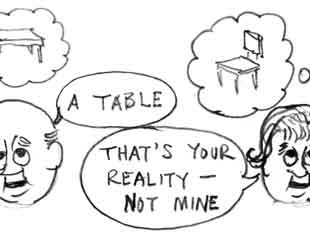

So we first sense the world, then we think about it and try to understand it. We learn about reality by abstracting from our experience of reality. That reality includes other people who can teach us what they have learned from their experiences. We exchange thoughts using symbols (like words, or pictures) with others. We learn to navigate an ordered universe. Let’s call this way of looking at the world Realism.

The second way of looking at the world is essentially the opposite. The second way does not trust the information that comes to the mind from the senses. I think I see a table over there, but how do I know for certain that my eyes do not deceive me? All I can say for sure is that I think I see a table. The only thing I can be sure of are my thoughts. Oh, and because I am sure I have thoughts I know I must exist–cogito ergo sum! But that is all I know for certain. Everything that appears to be an ordered universe is in fact my mind’s projection. Because ideas are the only things which exist for certain according to this point of view, we can call it Idealism (not to be confused with the laudable goal of having ideals to which to aspire!).

These two ways of looking at the world, Realism and Idealism, naturally produce two very different kinds of architecture. Realism leads to an architecture which has something to say about reality, and which orients Man in that reality. It is an architecture of symbols with specific meanings understood by others. Through those symbols, Man lives his place in an ordered universe. Because those symbols represent objective realities, we can call this kind of architecture representational architecture. It is traditional architecture.

Bath Abbey and surroundings, built on the solid idea Sum Ergo Cogito, I am therefore I think.

(Image Source)

The second way leads to an architecture which must necessarily avoid any suggestion of order or legible symbol. Since every man’s thoughts are ostensibly his only reality, symbols would be an offense, an imposition. So buildings can do no more than provide an emotional stimulus and they cannot pretend to orient one way or another. Man has no predetermined place in the universe–each man determines his own place.

Alois Jirasek (left) has a few choice thoughts about Frank Gehry’s office building in Prague.

(Image Source)

This second way of looking at the world makes very little logical sense, of course, for why should I assume someone out there actually exists whom I might offend? If all I can be sure of are my thoughts, then it makes no sense whatsoever even to speak to others or to build.

The Idealist immediately encounters a problem, however, as he is faced with the undeniably objective prospects of his own hunger, sickness, and death. He must make a compromise with his principles as he must engage with others in practical projects which have a bearing on his material existence. He promises that all other questions, those bearing on ultimate meaning and morality, will remain locked up in his private mind. Thus the “philosophy” called Pragmatism is born.

The architect who builds for the pragmatist has a little more of a palette to work with now–the forms of the industrial revolution, the forms of Progress. Pragmatist architecture is all about exposing beams, bolts, and ductwork–the things which make us comfortable, keep us safe, and increase our life span.

Pompidou Center, Paris

(Image Source)

Pragmatist architecture (to use the term loosely) nevertheless remains the child of the mistaken idea that we cannot know the world and learn our place in it. We can know something of the world. We have no choice but to trust our sense perception. People who have not taken leave of their common sense understand this, and instinctively sense the problem with the architecture.

If Samuel Johnson were alive today, I believe he would refute the modernists the same way he refuted the Idealist George Berkeley. From James Boswell’s Life of Johnson:

After we came out of the church, we stood talking for some time together of Bishop Berkeley’s ingenious sophistry to prove the non-existence of matter, and that every thing in the universe is merely ideal. I observed, that though we are satisfied his doctrine is not true, it is impossible to refute it. I never shall forget the alacrity with which Johnson answered, striking his foot with mighty force against a large stone, till he rebounded from it, ‘I refute it thus.’

Thank you for this well-written entry, which I think is informative and insightful.

Question of representation in architecture must be treated in different way than in literature, painting or sculpture. Though I understand the difference between “Plato’s and Aristoteles’ architecture”, I would say that the representation in architecture touches more general aspects of reality (beuty-loving, beauty-contempt/rejection, non-sense/absurd world, world full of order and human passion). It is not that (post)modernist unhuman (dis)order must be representatnion of idealistic nihilism. (Though it can be indeed.) It can as well be effect of MISUNDERSTOOD reality. Especially by omitting of some parts of human nature (anti kallotropism).