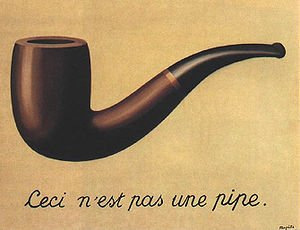

In 1929 the Belgian painter Rene Magritte unveiled his iconoclastic work “The Treason of Images.” Below the image of the pipe is the statement “This is not a pipe.” The man apparently was scrupulous enough not to want to lie to his audience, yet not so scrupulous as to have minded boring the audience with the obvious: neither the image of the pipe nor the word “pipe” are actual pipes, they are symbols for the thing we know is a pipe. Even a child can grasp that.

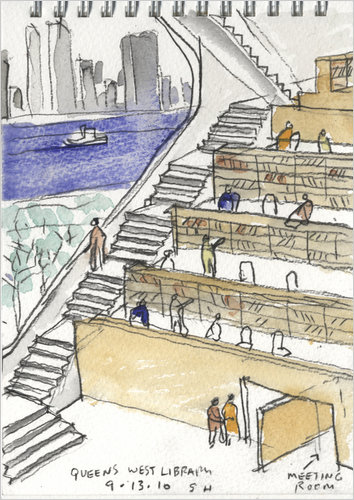

Magritte wanted to destroy the image, and he succeeded. Now that iconoclasm is De Fide among the undogmatic, a curious reversal has taken place. While it used to be that words and images symbolized things, now they have become the things themselves. For example, we are told that this is a library.

Ceci est une bibliothèque.

[Image source]

Without the label “library” on this pile, however, there would be no way to know that it is a library. The word is necessary to substitute for the thing. For this, my friends, is in fact not a library–it is a meaningless lump.

Designed by Steven Holl, the lump will house books for the denizens of the Hunters Point neighborhood in Queens, New York. The architecture critic for the New York Times heaps predictable praise upon it, using many words, words that have no relation to things. I give them a good fisking below for the convenience of readers.

+ + +

Civic Engagement Trumps ‘Shhh!’

By NICOLAI OUROUSSOFF

There may be no better example of the worrying state of American architecture than the career of Steven Holl.

At 63, this New York architect is widely considered one of the most original talents of his era. His work has influenced a generation of architects and students. And over the last decade or so he has become a star in faraway places like Scandinavia and China, where he is celebrated as someone able to imbue even the most colossal urban projects with lyricism.

Yet his career at home has been negligible. He has had only a handful of notable commissions in the United States, and his output in New York is embarrassingly slight: a modest addition to Pratt Institute’s school of architecture, a cramped (if underrated) gallery at the edge of Little Italy and a handful of interior renovations.

So when the Queens Library Board of Trustees approved the design of the new Hunters Point community library this month, it was a well-deserved and long overdue breakthrough. The project, done in collaboration with Mr. Holl’s partner Chris McVoy and scheduled to begin construction early next year, will stand on a prominent waterfront site just across the East River from the United Nations. It is a striking expression of the continuing effort to shake the dust off of the city’s aging libraries and recast them as lively communal hubs, and should go far in bolstering the civic image of Queens. [I struggle to find anything civic about this building. It is pure self-indulgence foisted upon a community, the very antithesis of civic.]

The building’s beguiling appearance — with giant free-form windows carved out of an 80-foot-tall rectangular facade of rough aluminum — should make it an instantly recognizable landmark [perhaps for all the wrong reasons]. Seen from Manhattan, it will have a haunting presence on the waterfront, flanked by the red neon Pepsi-Cola sign to the north and the remnants of an abandoned ferry terminal to the south. At dusk the library’s odd-shaped windows will emit an eerie glow, looking a bit like ghosts trapped inside a machine. And late at night, when the building is dark, spotlights will illuminate its pockmarked facade and the windows will resemble caves dug into the wall of a cliff. [Why a haunting presence, an eerie glow, ghosts, and a cave are desirable or relevant is left unstated.]

At night, the proposed lump is designed to be a blur.

[Source: New York Times]

Only at the site itself, however, will the optimism driving Mr. Holl’s design come into focus. [Optimism? What makes this building optimistic?] The library will stand at the western edge of Queens West, a soulless mix of generic apartment towers and barren streets built up in the last decade or so that has neither the dilapidated charm of the old manufacturing neighborhoods to the east nor the density of a real urban neighborhood. (The development’s one saving grace is a narrow park that snakes along the riverfront; its steel gantries, once used for loading boats, are an ode to the area’s industrial past.) [Alas, this building will add to the soullessness.]

Mr. Holl ’s design is not about escaping this world but transforming it into something more poetic. [Irrational shapes do not poetry make. True poetry is intelligible and conveys meaning. This building offers nothing substantive.] Approaching from the towers across the street, visitors will enter a tranquil reading garden, a little paradise walled off from the gloomy scene that surrounds it. Ginkgo trees will shade the garden, partly blocking the view of the towers. As visitors move closer to the library, they will be able to see through the lobby windows and out over a reflecting pool and the riverfront park. Other odd-shaped windows will allow diagonal glimpses up through the building and out to the sky. [It’s a pity that this library seems to be giving up on the contributing to the street, the very first thing a civic building is supposed to do. It’s telling that a site plan and a ground floor plan are not provided to us.]

When I first saw a rendering of this facade it brought to mind Gordon Matta-Clark’s 1975 “Day’s End,” in which Matta-Clark used a power saw to carve big circular openings into the exterior of an abandoned industrial building on the Hudson River in Lower Manhattan. In both works the overscaled cut-out openings are powerfully metaphorical. They suggest the desire to expose private, interior worlds to public scrutiny, and — by seeming to undermine the buildings’ structural stability — they evoke an unstable, ever-changing world. [First, such a juvenile sculptural statement hardly rises to the level of metaphor. Metaphors have depths that reward plumbing. Second, if this is supposed to be a public library, how is the metaphor relevant? A public library is by definition open to public scrutiny. It is not a private, interior world. Holl’s library is certainly not the first to have large windows. Finally, is there any point in evoking an unstable, ever-changing world? It’s all around. The point of these kinds of institutions, particularly libraries, is to be a kind of anchor, a signpost. Signposts are what distinguish civilized life from life in the jungle.]

Apparently even a regular door is too recognizable a type for Holl who provides a pivoting section of wall for access to the Meeting Room. Quite impractical.

[Source: New York Times]

But Mr. Holl’s design is also a statement about the individual’s place in a larger communal framework. The lobby is a towering space framed on both sides by several big, balconylike reading rooms. To get to them visitors climb a staircase that runs up the lobby’s back wall and past one of the huge free-form windows that afford views of the East River and Manhattan. The stairs lead first to the main reading room, which overlooks the lobby, then cross back to a children’s area or continue up to another reading room for teenagers. Eventually they emerge onto a rooftop terrace, where during nice weather people will be able to attend lectures and performances, or , when nothing is going on, lounge around and enjoy the spectacular view. [Again, what do these words have to do with the reality? The very opposite of a communal framework is suggested here. Communities share certain values in common, and they express those values through commonly understood symbols, be they words or images. Here the building offers a mere view of other people. But a view is no substitute for the things that bind men together. A crowd is not a community.]

The strength of this layout is that it allows Mr. Holl to balance the reader’s need for solitude with a strong sense of community. The main reading room, cantilevering out over the lobby, is the most open. The children’s reading room, the noisiest, is enclosed behind a curved wall with a few small windows cut into it so that kids can look across to the adults or up to the teenagers. [This is crowd control, not the binding together of a community.]

But it is the constant reminders of the larger world provided by the giant cuts through the building’s surface that give the design so much resonance. Mr. Holl is not interested in creating a monastic sanctuary; he wants to build a monument to civic engagement. The views aren’t just pretty; they remind us that the intellectual exchange of a library is part of a bigger collective enterprise. It’s a lovely idea, and touching in its old-fashioned optimism. [Sorry, Nicolai, the windows…er, “giant cuts,’ do not resonate, they are banal. A monastery is infinitely more engaged with the civitas than this lump. In fact, it provides a model for any community in search of the common good. This building, in stark contrast, through its specific avoidance of the symbols and types which make up the identity of our culture, isolates all the individuals who aspire to become a part of a “bigger collective enterprise.” Each is left to his own devices, each babbling a private language no one else understands, striving vainly to impose meaning on the void.]

+ + +

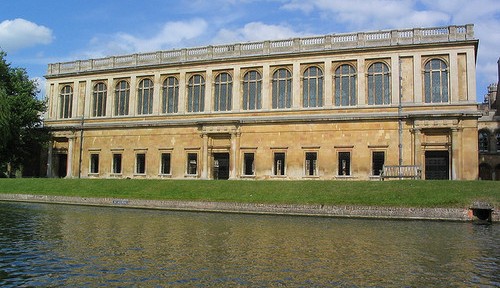

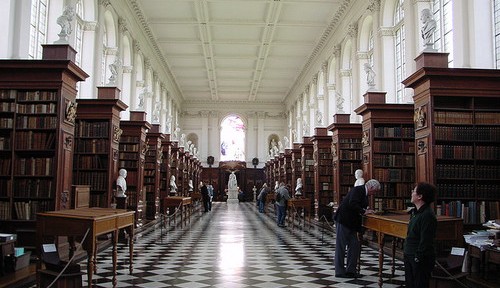

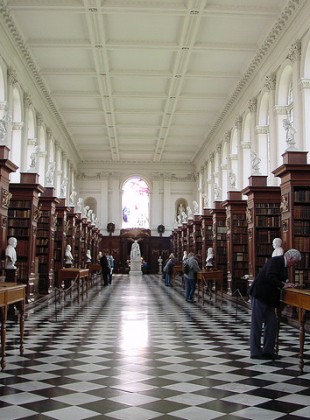

Now this is what a library is supposed to look like.

Wren Library, Trinity College, Cambridge. Large windows and everything.

[Image source]

I propose it as a source of inspiration for the library at Hunters Point. A smaller variation of course. It would compare appropriately with the main branch of the New York Public Library in Manhattan. A work of architecture of this dignity is the only way to bolster the civic image of Queen’s. While the building may look expensive, I can assure you good design costs no more than bad design. In fact, it’s cheaper, particularly over the long run.

There’s no mistaking this for a Louis Vuitton outlet.

[Image source]

Such a design would suggest that what our forebears have given us is not all for naught. We can continue the civilizing project they continued when it was handed to them. That is true old-fashioned optimism.

This is the first time i read a criticism of you, without being at architect, a library should reflect the history and culture, and also the peace that is the essence of this place.Honestly to me the only thing that inspires me is a vacuum!

Classical architects like to make superficial diagnostics at contemporary architecture. In an attempt to spread rhetoric which is ultimately…. intellectually and spiritually oppressive

You’ve got it exactly backwards, Mr. Kahn. There’s nothing superficial about our diagnosis of contemporary practice. I would argue we understand what contemporary practitioners are doing, and not doing, better than they do.