The formidable Roger Scruton, writer and philosopher, is always worth reading on the subject of architecture. He’s written several commendable books and occasionally produces a good, pithy article. This latest one, an opinion piece published in the Times of London, is quite trenchant, and even provoked an angry response from Jonathan Glancey, architecture critic of The Guardian. The latter, far from providing a credible rebuttal, however, rather showed himself to be out of his depth. I append the Scruton piece below with commentary interspersed.

+ + +

By Roger Scruton

If you were to ask what is the most perspicuous sign by which a civilisation is known, the answer must surely be the city. It is through the city that human beings have marked the Earth as a place of collective faith, freedom and festivity. It is in the city street and city square that people meet in friendship and commerce, and the classical styles of vernacular architecture are designed to record and emphasise the freedom and order of a society at peace with itself. [That is a beautiful sentence.]

If the ideal city that I have just described seems more and more a thing of the past, then we should not neglect to assign a due proportion of blame [a large proportion!] to the people who now call themselves architects. Public projects in our cities are routinely assigned to one of a tiny band of “starchitects”, chosen to design structures that will reliably call attention to themselves, and stand out from their surroundings.

Most of these starchitects — Daniel Libeskind, Frank Gehry, Richard Rogers, Norman Foster, Zaha Hadid, Peter Eisenman, Rem Koolhaas — have equipped themselves with a store of pretentious gobbledegook with which to explain their genius to those who are otherwise unable to perceive it. [They also teach the art of goobledegook to docile students. It is mastered much more easily than the art of architecture.] And when people are spending money that belongs to voters or shareholders, they will be easily influenced by gobbledegook that flatters them into believing that they are spending it on some original and world-changing masterpiece. The victim of this process is the city, and all those who have cherished the city as a home. [To be fair, some of the blame rests on the shoulders of our leaders who, for the sake of political expediency, are only too willing to erase the record of a society’s traditional order.]

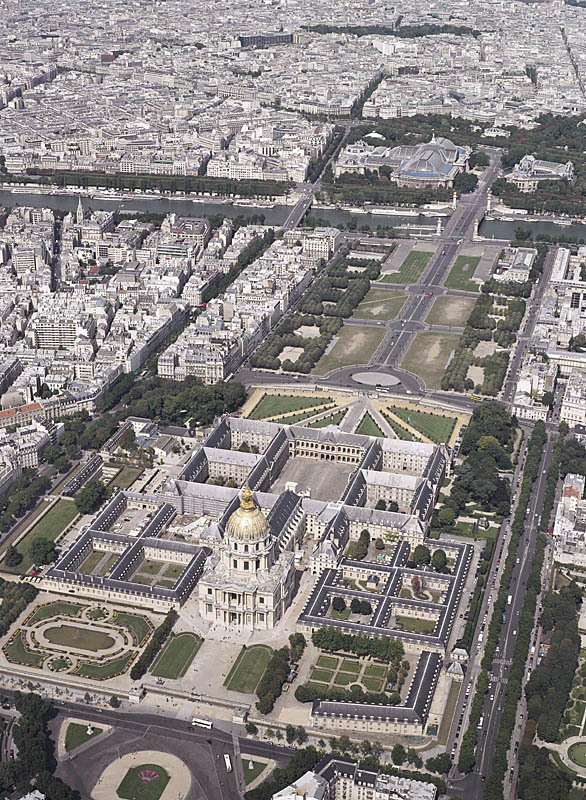

There have been architects who are geniuses — Michelangelo, Palladio, Frank Lloyd Wright. But a city is not the work of geniuses. It is the work of humble craftsmen and also the by-product of its own continuing conversation with itself. A city is a constantly evolving fabric, patched and repaired for our changing uses, in which order emerges by an “invisible hand” from the desire of people to get on with their neighbours. That is what produces a city such as Venice or Paris, where even the great monuments — St Mark’s, Notre Dame, the Place Vendôme, the Scuola Grande di San Rocco — soothe the eye and radiate a sense of belonging. In the past, geniuses did their best to harmonise with street, sky and public space — like Bernini at St Peter’s Square — or to create a vocabulary, as Palladio did, that could become the lingua franca of a city in which all could be at home.

[Here I beg to differ. A city that has been worked on by geniuses is blessed indeed. Would Rome be so great without the work of Apollodorus of Damascus, Michelangelo, and Bernini? Would Paris be so memorable without Hardouin-Mansart, Gabriel, and Haussmann? Humble craftsmen guided by sturdy traditions can produce good cities and places one can call home, it is true. But it takes geniuses to produce great cities. The hands that built the defining parts of Rome, Paris, and Venice are not at all invisible.]

Les Invalides, Paris, a home and hospital for aged and unwell war veterans.

Louis XIV commissioned architects Libéral Bruant and Jules Hardouin Mansart.

[Image source]

In contrast, the new architecture, typified by Gehry’s costly Guggenheim Museum in Bilbao, by Norman Foster’s lopsided City Hall in London, by Richard Rogers’ kitchen-utensil Lloyds Building, or by the shiny gadgets of Zaha Hadid, is designed to challenge the surrounding order and to stand out as the work of some inspired artist who does not build for people, but sculpts space for his own expressive ends.

[The problem is not the inspired artist per se — Michelangelo and Bernini truly were inspired. The problem arises when the artist’s subject is himself. Michelangelo and Bernini left Rome more Roman. The starchitect, in contrast, leaves a personal stamp (usually the middle finger) leaving a place with less of its identity than it had before.]

This approach to architecture is encouraged by the professional bodies and the schools, such as the remorselessly trendy Architectural Association and the Royal Institute of British Architects. Few schools of architecture now teach students to draw townscapes, façades or the human figure[or to draw anything at all!]; few teach students to compose using the classical orders, or to draw such meaningful architectural effects as the fall of light on a Corinthian capital — necessary skills that train the hand and the eye, and which teach architects to observe things more interesting than themselves. [More importantly, in my opinion, few teach history in such a way that students might understand how the architect’s work extends the social order he is dealt.] Engineering, isonometric drawing and smart computer imaging have replaced all that, and the rest is hype; deconstructionist gobbledegook designed to sell whatever piece of space-sculpture you can come up with. [Computer imaging has not truly replaced drawing, of course. Students are made to believe that their computer-generated renderings successfully represent their designs; however, all they usually produce are posters whose incomprehensibility is mitigated only by a strong graphic appeal.]

We should not be surprised, therefore, if the “works of genius” that our city planners are constantly permitting or commissioning have the appearance of things other than architecture: of vegetables, vehicles, hairdryers, washing machines or backyard junk. Often they are named after the alien object that they most resemble, such as Renzo Piano’s Shard now growing by London Bridge. That which makes a building into architecture, which is the ability to embellish a location and to enhance it as a home, is the aspect of building that architects no longer learn. [This difference says it all. The former, abstraction which can call to mind anything to anyone, is the fruit of the complete collapse of epistemology and the subsequent atomization of society. The latter, representation which calls to mind specific meanings understood by a people, is the fruit of a common sense view of reality, which we can come to know and which binds us together.]

It is often argued that modern constraints make it all but impossible for architects to behave as their predecessors did, veneering buildings with some eclectic reminiscence of the classical or Gothic styles, placing dressed stone over iron frames, or crowning the street façade with a Vignolesque cornice in tin. What were once cheap solutions to a shared public demand for ornament and order have become forbidding costs. Space is limited, skilled labour rare and gargantuan engineering well understood and relatively inexpensive — and that is why we look to the starchitects, since they authorise what would otherwise seem like vandalism on a massive scale. [I recommend reviewing that paragraph, it’s such a dense summary.]

To refute that argument is easy — you just have to look at the work of those public-spirited classical architects still working in our cities who have learnt how to construct buildings that fit so well into their surroundings that you notice them only in the way you notice friendly people in the street. Look at the commercial building just finished by Robert Adam next to St James’s Piccadilly, for example, or Quinlan Terry’s seminal Richmond Riverside. These buildings are not only less costly per square metre than just about anything by Rogers or Foster, they will also last longer, since they are able to change their use. [And look at our work, of course! For a great fund of skilled labor, we might also go to the sectors of historic restoration and high-end residential. There are plenty of excellent craftsmen out there who would love to do new public work.]

The typical starchitect building is without a façade or an orientation that it shares with its neighbours. It often seems to be modelled like a domestic utensil, as though to be held in some giant hand. It does not fit into a street or stand happily next to other buildings. In fact, it is designed as waste: throwaway architecture, involving vast quantities of energy-intensive materials, which will be demolished within 20 years. [Often, these buildings use “green technology” as a fig leaf. Nothing wrong with solar panels and the like; however, is there much point to solar panels if the energy they generate is being used to air condition a glass tower, i.e., a greenhouse? Building in a way which is not wasteful of precious resources begins with good design.]

Townscapes built from such architecture resemble landfill sites: scattered heaps of plastic junk from which the eye turns away in dejection. Gadget architecture is dropped in the townscape like litter, and neither faces the passer-by nor includes him. It may offer shelter, but it cannot make a home. And by becoming habituated to it we lose one fundamental component in our respect for the earth. [For the earth? Not sure I understand that conclusion. I was expecting “our human nature” or “our shared values.” In any case, a most valuable essay.]

If you enjoyed that, you might also enjoy Scruton’s video “Why Beauty Matters.” There are lots of wonderful insights there as well. His reliance on Kant is more obvious, however — a weakness. For example, he suggests that beauty gives us hope, but seems unclear as to what we ought to hope for. And his equation of beauty and the sacred just does not make much sense. Nevertheless, in the current climate, Roger Scruton provides good guidance. Temper him with a little Etienne Gilson (especially The Unity of Philosophical Experience) and you’ve got yourself an excellent intellectual foundation on which to build a city you can call home.

![Les Invalides, Paris, a home and hospital for aged and unwell war veterans.

Louis XIV commissioned architects Libéral Bruant and Jules Hardouin Mansart.

[Image source]](https://www.marcantonioarchitects.com/blog/wp-content/uploads/2011/05/Invalides_aerial_view.jpg)

![Les Invalides, Paris, a home and hospital for aged and unwell war veterans.

Louis XIV commissioned architects Libéral Bruant and Jules Hardouin Mansart.

[Image source]](https://www.marcantonioarchitects.com/blog/wp-content/uploads/2011/05/Invalides_aerial_view-310x420.jpg)

Thank you for this post, and the link to Scruton’s video. Do you have a specific recommendation for one of his books on this topic, or perhaps some other works which don’t have a flavoring of 18th C. Enlightenment views such as Kant? I have found it difficult to find works which tackle both the theological and artistic ideas of Beauty. Perhaps, I am mixing the application with the theory. I have struggled with some of the issues that he brought up when I attempt to design. In the end, it is my hope that what I can design will be Beautiful, but I know that if I strive for that as my end, it will certainly not be. It would seem to me that the only way to conscientiously create Beauty would be to strive to glorify God through your work and design. And as a result, Beauty would reveal itself. Thanks again for all the thought provoking posts.

The best is to read Alberti's Ten Books. Before you can truly understand that, however, you need a foundation in traditional Western philosophy and theology, especially Aristotle and St. Thomas Aquinas. If you have no such background, start with Aristotle for Everybody by Mortimer Adler, and The Dumb Ox by G. K. Chesterton. Then go through the primary texts, especially Plato's Republic, Aristotle Nicomachean Ethics, St. Augustine's City of God, and St. Thomas' Summa Theologica. Do all that and you're on your way.

Thank you for the direction, especially the bridging books. r