St. Germanus states regarding the ciborium:

The ciborium represents here the place where Christ was crucified; for the place where he was buried was nearby and raised on a base. It is placed in the church in order to represent concisely the crucifixion, burial, and resurrection of Christ.

It similarly corresponds to the ark of the covenant of the Lord in which, it is written, is His Holy of Holies and His holy place. Next to it God commanded that two wrought Cherubim be placed on either side (cf Ex 25:18)–for KIB is the ark, and OURIN is the effulgence, or the light, of God.

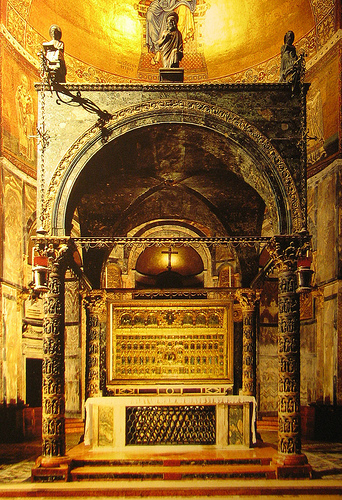

The ciborium at San Lorenzo Fuori le Mura, Rome. (The bishop’s cosmatesque

cathedra is visible behind the altar.)

(Image source)

Think of the ciborium as a room, the ark of the covenant writ large. The church building, like the Temple at Jerusalem on which it is modeled, is a succession of rooms, each progressively more holy, and therefore, smaller: from forecourt, to nave, to schola cantorum, to apse (or sanctuary), to altar. If the apse represents Heaven, then the ciborium represents that which is above heaven. In fact, curtains used to hang between the columns so that, at the most sacred moments of the liturgy (i.e., the Canon), the curtains were drawn and the altar was entirely out of view, just as God is out of view.

The 13th C. ciborium at the Basilica of San Marco, Venice. The oriental alabaster columns are covered in bas-relief sculpture depicting scenes from the New Testament. (Beyond is the exquisite retable, the Pala d’Oro.)

Most ciboria have four columns, coherent with the four corners of the altar. The square symbolizes the earth on which Christ was crucified and in which He was buried. And to symbolize the heavenward movement of the Resurrection, most ciboria are domed in some way. The dome can either be circular or eight-sided (as the Resurrection happened on the eighth day). The ciborium at the Hagia Sophia, with which St. Germanus the Archbishop of Constantinople would have been intimately familiar, was described this way by Paulus Silentiarus:

[720] And above the all-pure table of gold rises into the ample air an indescribable tower, reared on fourfold arches of silver. It is borne aloft on silver columns on whose tops each of the four arches has planted its silver feet. And above the arches springs up a figure like a cone, yet it is not exactly a cone: for at the bottom its rim does not turn round in a circle, but has an eight-sided base, and from a broad plan it gradually creeps up to a sharp point, stretching out as it does so eight sides of silver.

At the juncture of each to the other stand long backbones which seem to join their course with the triangular faces of the eight-sided form and rise to a single crest where the artist has placed the form of a cup. The lip of the cup bends over and assumes the shape of leaves, and in the midst of it has been placed a shining silver orb, and a cross surmounts it all. May it be propitious! Above the arches many a curve of acanthus twists round the lower part of the cone, while at the top, rising over the edge, it terminates in upright points resembling the fragrant fruit of the fair-leaved pear tree, glittering with light.

This spectacular ciborium no longer exists, unfortunately. Imagine the ciborium from San Lorenzo, top, with arches instead of colonnettes above the entablature, and covered in highly elaborate silver. Now imagine walking into the vast space of the Hagia Sophia–your attention would have been drawn immediately to this wonder of wonders. The altar, which would have been lost in its vast space without the ciborium, now becomes the focal point.

But the ciborium is not only for those on the outside looking in. Severus of Antioch tells us that it is “to show us who perform the priestly functions that we stand inside heaven, following the example of the incorporeal armies, and we celebrate mysteriously the holy rites.” (Homily 100)

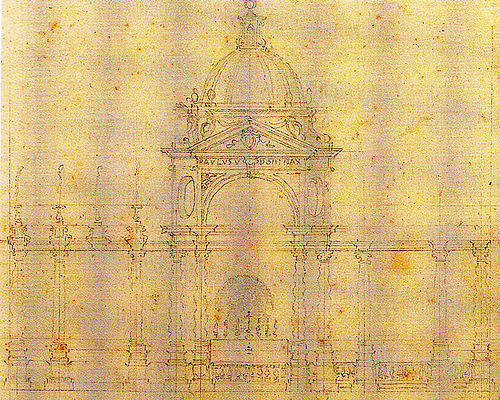

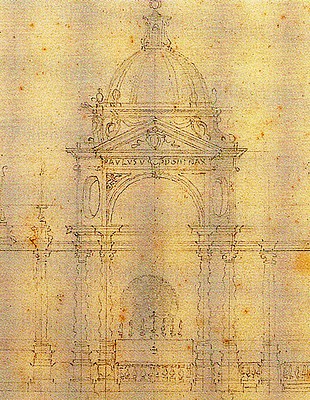

The ciborium should not be confused with the baldacchino which is a silken canopy held aloft on staves or suspended from above. We’ll be seeing them soon in Corpus Christi processions around the world. The famous baldacchino at St. Peter’sin Rome is actually a combination baldacchino and ciborium. When Paul V enlarged the apse, he found he had to build a second altar as the altar over St. Peter’s tomb was now too far away from the bishop’s throne. So as not to have two competing altars and ciboria, the altar over the tomb was covered with a baldacchino. (Bernini later monumentalized it, to the chagrin of some contemporary critics.) The altar in the apse was given the ciborium. It no longer exists, but it is thought that it would have looked a lot like this design, by Francesco Borromini.

Closer to home is this quite original design by McKim Mead and White for the altar at the Church of St. Paul the Apostle, on 9th Avenue. I would love to see a Solemn High Usus Antiquiorthere some day.

The high altar at the Church of St. Paul the Apostle, New York City.

(Image source)

If you haven’t already, you should offer your perspective to Fr. Beloin at St. Thomas More chapel, since I know that at one point he was asking for input on how to “set off” the altar in the newly renovated chapel. I’m not sure that a ciborium is the answer, but you might have some insight.

I’ve always liked the ciborium magnum in the shape of a tent with many oil lamps suspended from the ceiling, together with a hanging eucharistic dove. The Byzantine style is a particular favorite of mine, but there are so many noteworthy examples in the Romanesque form popular in the west until well into the 12th century. These too are most beautiful, remain ever popular, and when used offer an opportunity to surround the altar with rich biblical stories in stone and metal. While allowing the altar, or holy table, to remain simply decorated with an antependium.I eagerly await the return of the curtains too. To be drawn before the altar and celebrant at the start of the Canon. That way the ciborium becomes a frame for the likeness of the curtain before the Holy of Holies. The symbolism hits one right between the eyes. It’s very powerful.