The altar is the central focus of the Christian religion. So, naturally, it is the central focus of every church building. St. Germanus is marvelously succinct about it:

The holy table corresponds to the spot in the tomb where Christ was placed. On it lies the true and heavenly bread, the mystical and unbloody sacrifice. Christ sacrifices his flesh and offers it to the faithful as food for eternal life.

The holy table is also the throne of God, on which, borne by the Cherubim, He rested in the body. At that table, at His mystical supper, Christ sat among His disciples and, taking bread and wine, said to His Apostles and disciples: “Take, eat, and drink of it: this is my body and my blood” (cf Mt 26:26-28). This table was prefigured by the table of the Old Law upon which the manna, which was Christ, descended from heaven.

Of all the parts of the church building, the altar is the most ancient in provenance with roots stretching deep into the book of Genesis. It is also, perhaps, the one element church buildings hold most in common with other religions. Many pagan religions involve sacrificial practices of one sort or another–from ancient Greek animal sacrifice, to the Aztecs who offered human victims to Huitzilopochtli, to the Hindus who beg the favor of Kali. It seems that man naturally understands that Justice demands some kind of sacrifice be offered to God or the gods. Burning the victim converts it to smoke, effectively sending it up into the celestial spheres. So the Jews were not unique with their altar-building.

The earliest reference to an altar in Sacred Scripture is Genesis 8:20 when Noah offered sacrifice after the flood. Its form was simple: a collection of rough stones set upright to support a sacrifice over a fire. Other such Altars of Holocaust (from holos and cauma, meaning a thing wholly burnt) followed Noah’s, those of Abraham, Isaac, and Jacob. There was no church to surround these altars. They were built out in the open, usually in a high place.

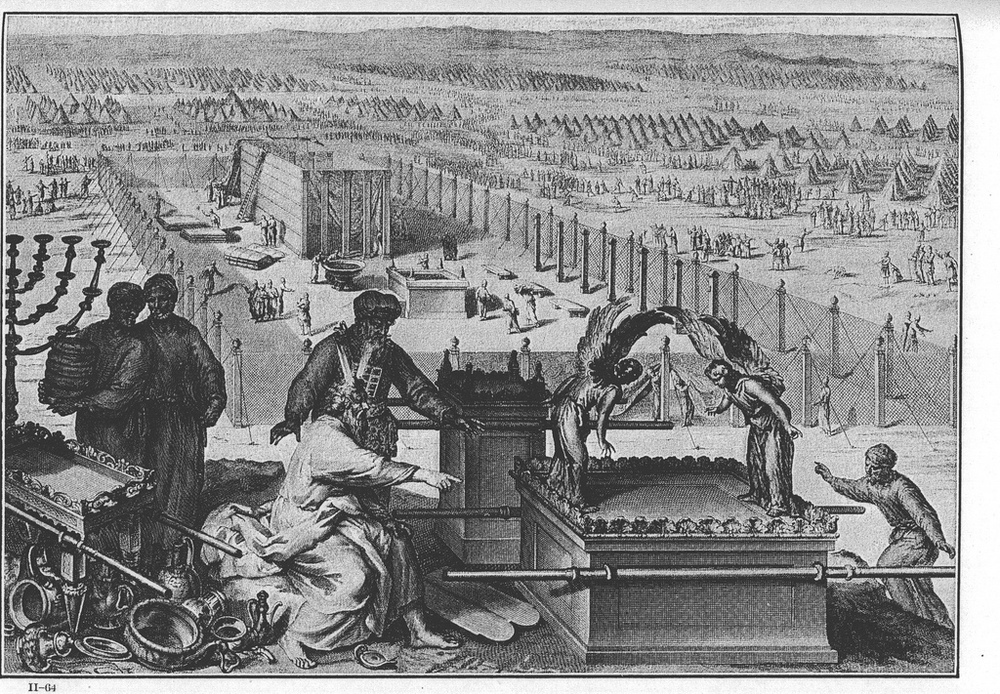

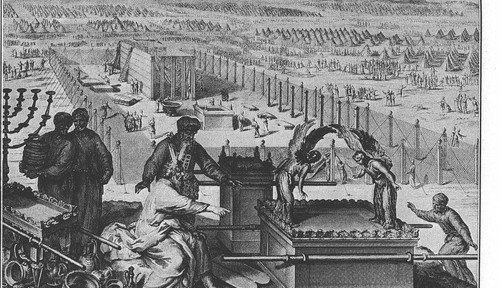

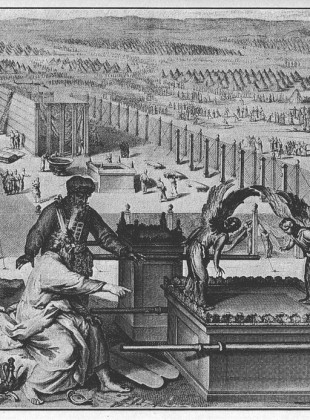

After the Hebrews were liberated from bondage in Egypt, when they roamed the desert, God revealed to Moses a precise form for the Altar of Holocaust. It was essentially a portable framework to contain a fire and support a grille. In addition, Moses was commanded to build the much smaller and more precious Altar of Incense. Built of an extremely durable wood called setim-wood and covered in gold, no victims were burnt on it. Finally, for our purposes here, Moses was commanded to build the Ark of the Covenant, a chest of setim-wood and gold which contained the Tables of the Law, the Rod of Aaron, and a golden urn containing a bit of the miraculous manna which fed the Jews for forty years. On top of the chest were the images of two Cherubims whose wings sheltered the chest.

In the image above, Moses points to the Ark of the Covenant in the right foreground. The Altar of Incense is just behind, and in the background in front of the Tabernacle is the Altar of Holocaust.

These three items were situated in hierarchical order in the Tabernacle, and in the Temple at Jerusalem. The Altar of Holocaust was outside the Temple proper, the Altar of Incense was in the Holies, the nave-like room inside the Temple, and the Ark of the Covenant was in the Holy of Holies, the most sacred room of all. Over top of the Ark, over the wings of the Cherubims, God’s presence was miraculously imaged as a cloud by day and a fire by night–the Shekinah. For this reason the cover of the Ark was called the Mercy Seat, or the throne of God, and the Holy of Holies symbolized Heaven. Indeed, the Cherubims surely hearken the Cherubims which guarded the gate of Eden after Adam and Eve were cast out.

The arrangement was like a narrative of spiritual progress–less bloody the closer one gets to Heaven. Blood was smeared on the horns at the corners of the Altar of Incense and merely sprinkled in the Holy of Holies only once a year on Yom Kippur, the Day of Atonement. The “mystical and unbloody sacrifice” is the natural next step. For St. Germanus also states that the Christian altar is prefigured by the table of the Last Supper, at which Jesus and the Apostles shared the Passover ritual.

Does he mean that the altar has become a table for a communal meal? Not really.

Passover commemorated that event which made the Altar of Holocaust, the Altar of Incense, and the Ark of the Covenant possible. “Moses and Aaron went in, and said to Pharao: Thus says the Lord God of Israel: Let my people go, that they may sacrifice to me in the desert” (Exodus 5:1). In return for each family’s sacrificing and eating a whole lamb and sprinkling its blood on their doorposts, God would liberate the Jews. The feast/ritual instituted to commemorate the event, the Passover seder, prominently features unleavened bread and wine. And at the Last Supper, Jesus commanded that the bread and wine substitute for the sacrificial lamb, and that He is the True Lamb which the Paschal lamb foreshadowed. The sacrifice has not become a memorial meal. Rather a memorial meal has become the Sacrifice, and the only way to undo the Fall and recover the Garden of Eden.

While the earliest Christian altars were built of wood (remember, the early Church was more or less an underground movement), stone altars became the norm as Christianity flourished–the better to symbolize the permanence of the New Covenant and Christ the Corner Stone. And from very early on, altars were built over the tombs of martyrs. The most spectacular examples are those which sit atop a confessio, which is a tomb that has a grate on one side, a fenestella, so that the faithful may see the relics of the saint.

The altar and confessio at San Giorgio al Velabro

(Image source)

The more typical altar has a simple stone box set in it, appropriately called the sepulchre, which contains a first class relic.

Altars are always four-sided, in imitation of their Old Testament forebears, to symbolize the four corners of the earth. In the Orient, the altars are perfect cubes. While the earliest altars were free-standing, in the West it gradually became the norm to move the altar against the wall out of a practical need for space for the ceremony. In the eastern rites, the altars are always free-standing.

The top, confusingly called the table, must always be of a single hefty piece of stone. The vertical supports for the table can be slabs called stipites (visible in the image above on the far right and left of the altar) or columns. The space between supports may be closed with stone panels, or left open. And panels, of course, can be highly decorated. Here is an absolutely gorgeous Cosmatesque altar in a truly sorry state in the crypt of Santa Prassede in Rome.

Altar in the crypt of Santa Prassede, Rome

(Photo by Fr. Lawrence Lew, O.P.)

Once the Spaniards had built an empire over which the sun never set, they could not be outdone by the Italians. Here is an altar that might make even King Solomon envious.

u didnt tell us the different parts of the altar

What about Saint Priscilla celebrating the Eucharist in the catacomb Fresco in Rome. There is an altar there. I know some men think it is not a mass because a woman is celebrating, but I am an Anglican woman priest and we all think it is obviously a Eucharist on a lovely altar